Note from publisher: This story was produced as part of an arm’s length collaboration with the Canadian Canoe Museum.

As a paddling enthusiast, I know that you don’t own a canoe as much as you have a relationship with one. Each is a unique character whom you gradually get to know as you venture together into the wilderness.

Mine is an 11-foot, 1963 Chestnut Featherweight made in New Brunswick, 38 pounds of shiny wood ribs clad in red canvas that has journeyed with me throughout New York State’s Adirondacks, Ontario’s Algonquin Park and the watery web of Quebec’s La Vérendrye Wildlife Reserve.

She has made me drunk with joy as we glided through landscapes I could never experience without her — sneaking up silently on beavers during misty dawns and out onto moonlit lakes, late at night. She’s also never failed to remind me of her annoyingly tippy tendency when I don’t execute a turn exactly to her liking.

Over the years, quirks and all, I’ve fallen madly in love with her. And while that may sound odd to non-paddlers, I recently learned that I am far from alone.

“We’ve arrived many mornings to find orphan boats left outside the doors with heartbreaking notes begging us to take in beloved canoes that can no longer be cared for,” says Jeremy Ward, curator of the non-profit Canadian Canoe Museum which is located, fittingly, in Peterborough, Ontario, where the famed Peterborough Canoe Company was born in 1892.

In 2006, when Farley Mowat gifted the museum his 16-foot, 80-pound, 1922-vintage Peterborough sailing canoe — a lifelong companion originally owned by his father — the iconic author referred to her as “sweetheart.”

I get it — which is why visiting the world’s only dedicated canoe museum with a collection of over 600 watercraft and 1,000 artifacts feels like a pilgrimage for me.

Photo by Margo Pfeiff

I confess I’m initially surprised to find this landmark collection housed in two non-descript former factory buildings hunched in a bleak industrial area parking lot far from water.

However, as I open the museum door, I’m instantly enveloped in a warm and welcoming world of lovingly constructed watercraft, a wealth of fascinating historical nuggets and intriguing Canoe-abilia sure to capture the imagination of even the staunchest non-paddler.

Photo by Margo Pfeiff

I am barely inside the foyer when singer Gordon Lightfoot’s yellow canoe dangles before me like a giant banana, an indestructible Old Town Royal X complete with bumps earned after being wrapped around a rock on the Nahanni River.

“It popped right back to shape,” Ward tells me. When I press a display button I bop along to Lightfoot’s “My Canary Yellow Canoe”; pushing another, I hear Lightfoot wax poetic about canoeing with the Tragically Hip’s Gord Downie.

Canoes bear names like Overwego, Humpty Dumpty and Cheechoo. The red canoe Pierre Trudeau famously paddled more than 1,000 miles from Montreal to James Bay is the Ça Ira, meaning “It’ll get there,” according to his son, Justin.

Photo by Margo Pfeiff

I feel Pierre present in spirit, peeking over my shoulder as I admire his famous fringed buckskin and his elegant birchbark canoe, a gift from when he wed Margaret Sinclair in 1971.

Gifting canoes, especially at weddings, is a big Canadian thing. I learn this while admiring a rack of gleaming, cedar-strip royal canoes, wedding presents from Canada (stored at the museum for long-term safe keeping) to Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip in 1947, and to Charles and Diana in 1981.

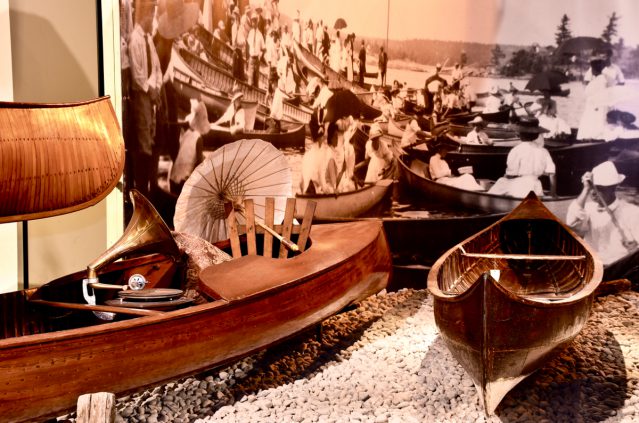

“And over here are Canadian courting canoes that were rented by young people for privacy in plain sight during the conservative Victorian era,” Ward explains.

While the man — often sporting a boater hat — paddled, the woman sat on cushions at the bottom of the canoe shaded by her parasol. The backrests, pillows and phonographs make me nostalgic for a time I never knew.

Canoedling was a term used at the time to describe cuddling in a canoe.

Photo by Margo Pfeiff

I prowl the museum’s two floors for hours. I’m intrigued by a sectional canoe for Klondike gold rush stampeders, designed to be schlepped in three parts over the Chilkoot Pass then snapped together to paddle the Yukon River to the gold fields.

And it is a treat to contemplate a painting by prominent Canadian artist Robert Bateman featuring his Minto canoe as it rests on a pond’s wooden dock. Alongside stands his actual boat, handmade by legendary Ontario craftswoman May Minto and painted green by Bateman himself.

In the museum workshop, retired fire chief Russ Parker builds a new kayak. As the onsite artisan and workshop instructor, he enthusiastically lists off courses where people can learn to make moccasins, anoraks, snowshoes and birchbark baskets.

There’s even a paddle-carving class which makes me truly sorry I can’t stay longer.

Parker is one of a vast cohort of volunteers that keeps the museum going. “About 140 volunteers are active weekly,” says executive director Carolyn Hyslop, “and we rely on their passion for sure.”

Photo by Margo Pfeiff

I realize how seriously the museum takes its mandate to engage young people when I spot Jen Burnard (seen above) in full coureur des bois regalia alongside a huge birchbark voyageur canoe as part of a regular Skype virtual museum field trip.

“We do this interactive exploration of our canoe world with over 4,000 students annually from India, Russia, Argentina — everywhere!” says Burnard, the museum’s lead animator. “Right now, we have kids ‘here’ from a two-room schoolhouse in northeastern B.C.”

As part of their many experiential youth programs, students can spend a night in the museum, sleeping in a birchbark Mi’kmaq wigwam or beneath a partly overturned canoe as voyageurs did in the fur trade days. This makes me seriously want to be a kid again.

“A nation of rivers….” I remember those words by geographer, explorer and author James Raffan as I gaze up at a 20-foot wide map of Canada with no place names or borders, just an intricately laced web of waterways from coast to coast to coast. No wonder Canada is synonymous with canoes.

“That was the Inuit and First Nations’ travel network for millennia and it continued on towards Alaska and Greenland,” says Robin Cavanagh.

Since roughly one-third of the museum’s collection consists of Indigenous watercraft, Cavanagh, a member of the Sagamok First Nation, was hired by the museum to work as director of Indigenous peoples’ collaborative relations.

Cavanagh points out massive West Coast cedar dugouts, different styles of skin kayaks and bark canoes representing peoples from the Inuit up north to Newfoundland’s Beothuk.

Jeremy Ward and Robin Cavanagh / Photo by Margo Pfeiff

I’m thrilled to meet James Raffan (the explorer I quote earlier), who works as the museum’s director of external relations and who is the author of Fire in the Bones — the biography of Canadian naturalist and canoeing guru Bill Mason.

Raffan escorts me to his favourite spot in the museum, a camp mess room exhibit where an 1890’s dugout canoe hangs above a picnic table.

“In 1957, that canoe became the first in camp director Professor Kirk Wipper’s collection at Camp Kandalore, north of Minden, Ontario,” says Raffan.

Wipper’s collection grew into the Canadian Canoe Museum which opened on Canada Day in 1997.

“I spent summers at Kandalore and the feel and sounds of this room — especially with kids visiting the museum, running around and playing with the interactive display’s melamine dishes — take me back to my early camp and canoe days.”

James Raffan with Farley Mowat’s sailing canoe / Photo by Margo Pfeiff

The museum collection is now so large that 80 per cent of it is archived in an unheated warehouse across the parking lot. When I continue my tour with Ward, and the curator unlocks and opens the warehouse’s small steel door, I literally gasp.

Inside, an enormous “canoe cathedral” features boats stacked as far as I can see.

This kaleidoscope of watercraft includes ornate dugouts from Papua New Guinea, Khlong boats from Thai floating markets, a round Welsh wicker coracle and the world’s biggest racing canoe collection, including sleek Kevlar and carbon fibre craft from the 2012 Olympics.

Alongside a battered, decal-covered fibreglass canoe called the Orellana, Ward tells me her story.

“Don Starkell and his son Dana paddled her 19,300 kilometres from Winnipeg down the Mississippi to the mouth of the Amazon River,” he says. According to what is now referred to as Guinness World Records (formerly The Guinness Book of World Records), this is the longest documented canoe trip in human history.

Ward draws my attention to an entire section of wooden dugout canoes recovered from mostly Ontario lake beds and river bottoms.

He’s also keen to show off a rare 17th-century birchbark canoe, possibly the world’s oldest, its maker unknown. Acquired by a British soldier who fought in Quebec during the American War of Independence about 250 years ago, it was discovered in a shed in Cornwall, England and donated to the museum.

“We have no acquisition budget for purchasing artifacts. For the most part, people reach out to us,” explains the curator. “We constantly get emails and letters from people — from Austria to Australia — with questions about their vintage Canadian canoes.”

Photo by Margo Pfeiff

Some may look like wrecks, faded, with torn canvases or broken gunwales, but each canoe at the Canadian Canoe Museum was at one time loved. And each boat comes to life with a story.

In some ways, the warehouse archives are the best part of my visit, a solo exploration among uncurated gems.

“That’s part of the reason,” says Ward, “we’re keeping the archive feel for much of the collection in the new museum.”

This spring, I’m excited to learn, the Canadian Canoe Museum will break ground alongside the Peterborough Lift Lock and the Trent-Severn Waterway (both Parks Canada National Historic Sites) for a $65-million masterpiece of contemporary design.

The ambitious plan calls for a low-key but stunning, 83,000-square-foot building with a green grass roof and glass walls.

When the new museum opens its doors in 2022, the non-profit operation will expand its educational programs, which include canoe lessons and canoe tripping camps.

“Imagine,” Ward says with a laugh, “we’ll actually have a canoe museum alongside water.”

Image courtesy Canadian Canoe Museum

Founded by two Canucks on the loose in a big country, Toque & Canoe is an award-winning Canadian travel blog. Feel free to follow our adventures on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook

David Finch commented:

GO TO THIS MUSEUM!!!

Every Canadian that has ever been in a watercraft of any sort – at camp, the cottage, on a river trip – deserves to explore the stories and smells and sounds of this museum.

Yes, sounds too. A waterfall in the middle of the museum ties together the fascinating exhibits with the cackle of water over rocks.

Donate to the Canadian Canoe Museum.

Shop online.

And most of all forward the link for this article to everyone you know.

Paddles UP! David Finch – Calgary

harri luukkanen commented:

Thanks for interesting information on CCM. And for good pictures. As a life-long paddler, kayaker, canoeist, and canoe sailor, this looks inpressive. I hope one day to visit your museum.

Here I have two notes to consider.

In city of Lahti, Finland, you can find another museum dedicated only to canoes and kayaks. The ‘Melontamuseo’ (or Paddling Museum) was founded by the Vesisamoilijat Canoe Club, Lahti, some 10+ years ago. Now the museum on the club site is registred as an official museum in Finland. The director of keeper of Melontamuseo is Mr Risto Lehtinen, an active paddler. You can reach him by email: risto.lehtinen@gmail.com.

The second issue for you to consider in my fortcoming book on canoe history, which may interest you. The book, ‘The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of Eurasian North’, written by me and William Fitzhugh, and published by Smithsonian Press, cast light on the little known canoes of European and Asian tundra and taiga canoes and some 40 native user folks along the inland and coastal waterfronts. Here, in the book you may learn more about the bark and skin canoes on the Old Continent, from Finland to Chukotka and Amur. Also about the history how the Siberian canoe builders created the canoes on New Continent.

Margo Pfeiff commented:

Harri – Thanks for your great information which I’ve tucked away for a future trip to Finland! As Toque and Canoe’s informal “canoe correspondent” I see perhaps another story, on tundra and taiga canoes, unfolding for this website. Happy paddling, Margo Pfeiff

Sandra Phinney commented:

This story just made my heart sing. It also transported be back to the museum, which I visited (and the warehouse!) several years ago. Memorable at so many levels.