Editor’s note: This story was produced as part of an arm’s length collaboration with Trans Canada Trail. Our post was not reviewed or edited by Trans Canada Trail before publication.

— By Kim Gray

You never know where a story will lead you.

I, for one, had no idea that writing about The Great Trail (formerly called the Trans Canada Trail) would re-unite me with an old friend. But there Dianne Whelan was, at the other end of the phone, sounding as full of life as she did years ago when we worked together as young journalists in Vancouver, B.C.

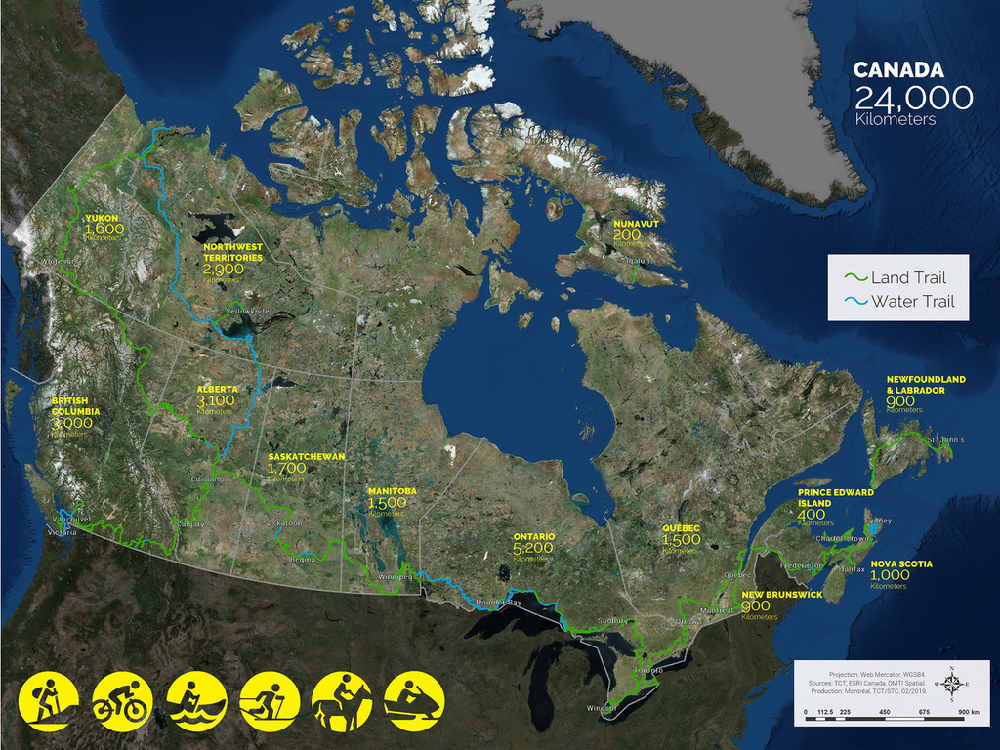

Whelan is on a quest to be the first person to hike, bike, ski, snowshoe, paddle and portage the entire length of Canada’s ambitious, 24,000-plus-kilometre “system of greenways, waterways and roadways.”

She began her adventure in 2015 when, in spite of her positive nature, the journalist-turned-filmmaker — of European ancestry with “Mi’kmaq blood on my mother’s side” — found herself becoming disillusioned with life.

“I remember hearing about a whale that was found dead on a beach with car parts in its stomach. I had a crisis of faith,” recalls Whelan, who has already clocked 14,000 kilometres after starting her journey in St. John’s, Nfld.

“It’s a scary place when the world stops making sense to you,” she says. “Travelling along this umbilical cord, through land and water that connects us all in spite of our differences, seemed like a way forward.”

Graphic courtesy Trans Canada Trail

Trans Canada Trail founders Bill Pratt (an Albertan) and Pierre Camu (a Quebecois) conceived the audacious idea for a great Canadian trail in 1992, when they were working as event planners on Canada’s 125th anniversary celebrations. In 2017, a quarter of a century later and during festivities for Canada’s 150th, the organization would salute the trail’s nation-wide connection with almost 200 gatherings countrywide.

Today, the world’s “longest multi-use recreational trail network” — which moves through urban, rural and remote wilderness landscapes from coast to coast to coast — continues to be a work in progress, while inspiring a bold new era of adventure in Canada.

“My dream is that this trail becomes embedded in the hearts and minds of Canadians as ‘their’ trail, that it feeds their hearts, bodies and souls and that it becomes the tie that binds us,” says Deborah Apps, president and CEO of Trans Canada Trail — the non-profit organization that oversees The Great Trail, which includes over 400 of Canada’s cherished community pathways, from B.C.’s Galloping Goose Regional Trail to Manitoba’s historic Crow Wing Trail to Confederation Trail on Prince Edward Island.

In Ottawa this past fall, the Royal Canadian Geographical Society awarded the Trans Canada Trail (and by extension, its thousands of volunteers and partners from around the country) a gold medal for remarkable “achievements in geography.” However, it’s important to note, says Apps, that “connection does not mean completion.” Her organization, she says, will continue to work closely with communities in all of Canada’s thirteen provinces and territories to enhance both visitor experience and safety on the ground into the future.

Valerie Pringle, former Canadian broadcaster turned Trans Canada Trail rainmaker, agrees that The Great Trail will only continue to evolve. “I see it as a multi-generational project. I see my grandchildren working on this,” says Pringle, who played a significant role in raising the $75 million required to make the trail what it is today.

“The vision for it is so moving. It’s about learning our history and geography and getting to know our communities,” she continues, encouraging Canadians (most of whom live within half an hour of the nation-wide trail) to find ways to get involved, whether it’s volunteering time, contributing financially or exploring the network of pathways for themselves.

“The Great Trail is really about being outdoors, which is good for everyone’s physical and mental health,” says Pringle. “It’s a phenomenal resource.”

Crow Wing Trail, Manitoba / Photo courtesy Actif Epica via Trans Canada Trail

No matter their length or location, trails are “desires written on the earth” shaped by the priorities of each generation of user, muses the author of the New York Times bestseller On Trails: An Exploration. “That’s what I love about them. They’re living things,” says Robert Moor from his home on Canada’s Sunshine Coast.

Moor, whose book was declared a “wanderer’s dream” by The Economist, describes a typical trail as something that physically emerges due to people travelling from one place to another, whereas long or “mega” trails happen in reverse.

“They appear first as an idea, then they take shape. The length itself creates an impetus to follow it,” says Moor, pointing to North America’s first “really long trail,” the Appalachian Trail, that inspired his book.

“The neatness, the boldness of the idea draws people to the Appalachian Trail. This is what mega trails are trading in or capturing — narrative power and the glow of adventure,” he continues, adding that it’s worth remembering that in 1921 the Appalachian Trail was just an idea. Today, an estimated two million people are reported to use it annually.

“I started hiking when I was ten. It allowed me to explore the inner contours of my own brain, and the outer contours of the world at large,” says Moor. “Hiking is hard. Wilderness is hard, by definition. It’s not easy or soft. It’s an acquired pleasure, one I’m grateful for, that’s good for your health and that strengthens you.”

Canada’s Great Trail, he observes, “highlights the continental vastness of the country, connecting all these disparate communities. I expect it will inspire a lot of people to take adventures they never otherwise would think to take.”

Of course, this is already happening, with each individual making his or her own unique mark on the impressive network. In November 2018, an Alberta man named Dana Meise distinguished himself by becoming the first Canadian to walk The Great Trail who reached all three coasts, finishing up in Tuktoyaktuk. His efforts were in honour of his father, who’d lost his ability to walk.

Meise’s journey was completed on the heels of Sarah Jackson‘s previous two-year adventure, which wrapped up in 2017 after she was the first woman to walk The Great Trail from west to east, starting in Victoria, B.C. and finishing in St. John’s, Nfld. Jackson was inspired by an uncle who hiked Spain’s Camino de Santiago. (Dianne Whelan, when she finishes her journey, will be the first to travel along the full 24,000-plus-kilometre trail from coast to coast to coast, waterways included.)

Painting by Cory Trépanier / Caledon Trailway, Ontario

Canadian artist Cory Trépanier, who painted the above landscape of Ontario’s Caledon Trail (the first section of The Great Trail to be formally recognized as part of the network), says that one of his goals as an artist is to bring people closer to nature.

“The trail is an extension of this idea for me. It gets individuals out there, smelling the fresh air and listening to the leaves in the trees,” says Trépanier. “I especially like that once you’re on the trail, you know you could just keep going, in either direction, right across the country. It’s a unifying notion in a time when there is so much divisiveness in the world.”

Trépanier is one of dozens of prominent Canadians who have enthusiastically lent their names in support of The Great Trail over the years as part of the Trans Canada Trail National Champion community.

Other “champions” include world-renowned anthropologist Wade Davis, Inuk singer Susan Aglukark, hockey player Sidney Crosby, author Margaret Atwood and more recently, extreme adventurer Laval St. Germain (the first Canadian to climb Everest with no oxygen) who tells me:

“I’ve travelled on iconic trails all over the planet, including the trail up Mount Everest’s north side. Even though the bite marks from my crampons on Everest’s summit vanished quickly in the winds, I wrote my story on that trail. It is as permanent for me as ink on a page.” St. Germain says he imagines one day “writing my own story on The Great Trail, with my boots or my bike. The idea holds tremendous pull for adventurers everywhere.”

On The Great Trail in Fundy National Park / New Brunswick / Photo by Ann Verrall

St. Germain’s comments bring us back to Whelan, seen in the image above, who is documenting (along with co-creator Ann Verrall) her lofty expedition in words and film, as well as in short CBC radio documentaries featuring people she meets on her travels.

“I’m searching for wisdom. I’m meeting elders, healers and grandmothers along the way, and I’m having profound exchanges,” she says. “I can tell you now that the despair I had in my heart is disappearing.”

Whelan, who hopes to finish in Victoria, B.C. by 2021, is currently teeing up for the next leg of her country-wide adventure, hiking, biking and paddling from Saskatchewan towards Alberta and then canoeing north to Tuktoyaktuk via the Athabasca, Slave and Mackenzie Rivers.

“Hey, I have an idea,” she says. “Why don’t you join me for a few days on the river?” I promptly respond “I’m in!” and she promises she’s going to hold me to her invitation.

It’s been ages since we saw one another. I imagine the fun of swapping tales around a crackling campfire at night with my unstoppable friend, her red canoe pulled up on the river’s edge and a star-filled sky above.

And I’m reminded, you never do know where a story — or a great trail for that matter — will lead you.

Founded by two Canucks on the loose in a big country, Toque & Canoe is an award-winning Canadian travel blog. Follow our adventures on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook

Sandra Phinney commented:

So happy to read this story! It’s full of wonder. Will be following this epic journey.