Publisher’s note: Our story was created as part of an arms length collaboration with Travel Manitoba.

— By Kim Gray

What comes immediately to mind is that we weren’t expecting to feel this way.

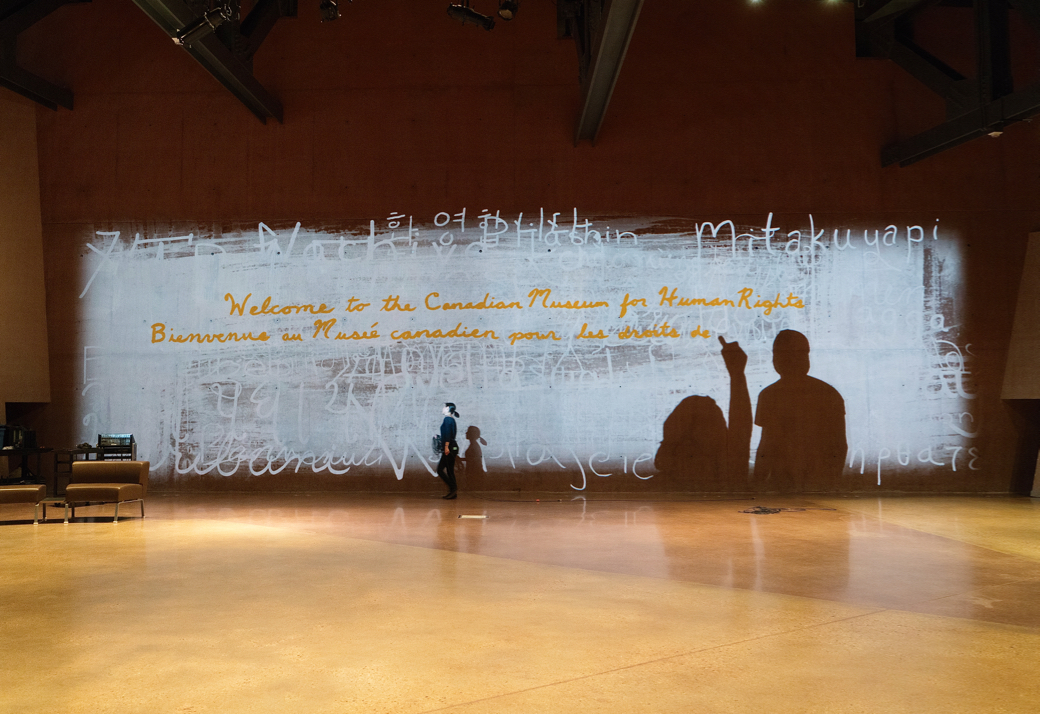

Last summer, Toque & Canoe co-founder Jen Twyman and I were en route home from a trip up north, when we paid a whirlwind visit to Winnipeg, Manitoba’s Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

Designed by U.S. architect Antoine Predock, the award-winning institution — originally conceived by the late Canadian visionary Israel Asper — opened its doors in 2014 at a cost of $351 million.

Given the museum’s reputation as an important newcomer to the global human rights conversation, we were keen to see it firsthand, even if we were on a tight schedule.

To our surprise, in spite of the museum’s challenging subject matter, we found the experience uplifting — so much so that we left eager to come back with the luxury of more time, time to give the museum the attention it warrants, of course, but also to explore why we felt this way.

Fortunately, we were able to return this spring.

We arrive before the museum opens on a sunny Saturday morning so we can take stock of the extraordinary building that now dominates Winnipeg’s skyline.

Located on Treaty One land where the Red and Assiniboine Rivers intersect, the structure features a glass exterior with 5,000 square metres of windows designed to represent the protective wings of a dove.

We’re comforted by this international symbol of peace, which is also referred to as The Cloud and which doubles as a mirror to the sky — just as we’re comforted by the friendly, life-sized sculpture of Mahatma Gandhi that greets visitors as they move to and fro on the outdoor pathways.

We decide that Gandhi would approve of the museum’s mandate which is “…to enhance the public’s understanding of human rights, to promote respect for others and to encourage reflection and dialogue.”

We choose to launch our visit with a guided tour, which we strongly recommend, leaving the afternoon for more independent exploration.

While more than 300 artifacts are on display in the museum’s 12 galleries, many of the installations are interactive or linked to multimedia technology.

Relying on an interpretive guide for expertise in this cutting edge environment is helpful, especially when your guide is clearly knowledgeable and passionate about her subject matter.

Given her Aboriginal ancestry, our host, Marilyn Dykstra, who belongs to the Cumberland House Cree Nation, brings forward a unique perspective, particularly on the subject of the estimated 150,000 Aboriginal, Métis and Inuit children who were separated from their families and forced to attend residential schools between the 1870s and 1990s.

What did Duncan Campbell Scott — Canada’s Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs from 1913-1932 — say? “I want to get rid of the Indian problem…Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic.”

Dykstra reminds us that she is grateful for the fact that, in spite of more than a hundred years of devastating government-sanctioned assimilation policies, Indigenous cultures can be observed thriving from coast to coast to coast in Canada.

As our guided tour, where we are joined by visitors hailing from Mexico to Nova Scotia, continues, we collectively fall silent in the Examining the Holocaust and Breaking the Silence galleries, absorbing stories of some of the most horrifying atrocities known to humankind.

What works, what stops us from utterly despairing as visitors to this courageous space, is that examples of human tragedy are balanced with those of triumph.

We learn about human rights heroes such as Canada’s Viola Desmond (our Rosa Parks), South Africa’s Nelson Mandela and Mareshia Rucker, a young woman from Georgia in the U.S. whose red prom dress is featured as a symbol of her stance against segregated proms, which continue to this day, at her old high school.

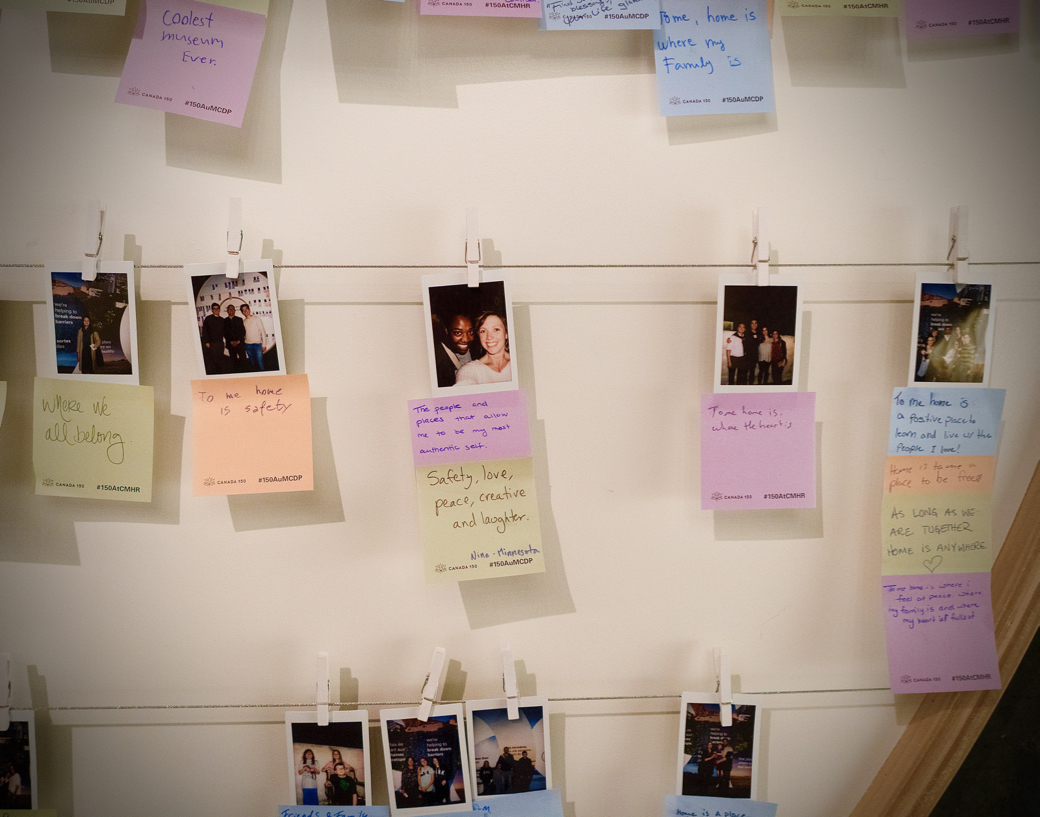

Near a “wedding cake” display of framed photos featuring same-sex couples in the Canadian Journeys gallery, we also learn about Winnipeg activists Chris Vogel and Richard North who, with the goal of generating positive publicity around gay relationships, bravely exchanged wedding vows at a Unitarian church in 1974.

There’s something to be said about experiencing the human rights conversation in community with others, with those partaking in our guided tour, but also alongside the general population of museum visitors who appear to come from all walks of life and every country imaginable.

The understanding is unspoken but we all feel it.

We may, in effect, be strangers but we sense our shared values. We’re here because we’ve decided that what the museum offers is important. That education is important.

Connecting with others in this context buoys us.

Ultimately, what moves us most about our experience at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights is the exceptional feeling of the place.

We’re talking about an atmosphere that fosters a safe and secure attempt at coming together, at dialogue, in a complex and hopeful human world.

This is where the light comes in.

Founded by two Canucks on the loose in a big country, Toque & Canoe is a blog about Canadian travel culture.

Catherine Hunter commented:

Beautiful photography! Really showcases the visual power of the building and exhibits!

Joel Lagimoniere commented:

Love it! My partner and I are pictured in the “Wedding Cake”. Top row, first picture on the right. We have to go to Winnipeg and see it for ourselves.

toque & canoe commented:

So awesome Joel! Thanks for your comment. We love it when our stories keep connecting with readers, even years later!