By Kim Gray

In our latest collaboration with the Indigenous Tourism Association of British Columbia, we’re featuring Indigenous tourism enterprises in B.C. with sustainability in mind, along with a few thoughts on travel’s latest buzz phrase, “regenerative travel.”

Simply put, regenerative travel refers to a travel experience that, ideally, enriches the lives of travellers while leaving a place in better condition than it was before.

The concept is being touted in the travel industry as more evolved, more reciprocally nourishing if you will, than what we’ve come to associate with green, eco or sustainable travel.

Given what I’ve learned about Indigenous tourism in the past decade, I’d suggest that “regenerative tourism” isn’t new.

In fact, the concept behind this latest tourism industry buzz phrase sounds much like the spirit behind the Indigenous travel experiences I’ve been writing about for years — experiences that put the well-being of people (future generations included), culture and nature front and centre.

As the world starts to move again and planet friendly adventurers want to make a difference with their travel dollars, here are 10 B.C.-based Indigenous tourism operations to put on your radar.

Be prepared, though. They may bring joy, wonder and new meaning — not to mention new friends and a deeper sense of Canada’s westernmost province — into your life.

Photo by Jennifer Twyman / Spirit Bear Lodge, Klemtu, B.C.

Spirit Bear Lodge

I visited Spirit Bear Lodge five years ago with Jennifer Twyman, photographer and co-founder of Toque & Canoe, and we still talk nonstop about the experience.

It changed us, demonstrating how Indigenous-led tourism in Canada is a powerful means for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people living in this country to come together.

The lodge, located in Klemtu on Kitasoo Xai-xais traditional territory, is in the heart of what is more popularly called The Great Bear Rainforest in British Columbia.

It was a privilege to get to know lodge guides Sierra Hall and Troy Robinson. We appreciated learning about the region’s ancient history and about how the lodge itself has helped revitalize local culture.

During our time in Klemtu, we communed with a curious humpback, shot video of a spirit bear doing a belly flop into a river (unforgettable) and supported the local art scene with the purchase of beautiful carvings.

Bridget Orsetti, who works on the lodge’s management team, says the operation’s guiding principle has always been driven by the well-being of community, land and wildlife.

“You’re going to be very comfortable when you visit, but we’re not offering a fancy package,” Orsetti explains. “The luxury you get as a visitor is to be with an Indigenous community and to hear their stories, to be part of their journey and to help protect something that is really special.”

Spirit Bear Lodge charges each guest a $200 conservation fee. Proceeds support the Guardian Watchmen Program (where Indigenous watchmen patrol the coast to protect the water and the estuaries), the Raincoast Conservation Foundation and the Kitasoo/Xaixais Stewardship Authority.

They also help support the Spirit Bear Research Foundation which, says Orsetti, “catalogues not just spirit bears but the full range of species in this area — from goat populations to tiny frogs. They’re all connected.”

Photo by S Hennigan courtesy the Haida Heritage Centre at Ḵay Llnagaay / Haida Gwaii, B.C.

Haida Heritage Centre at Ḵay Llnagaay

Thirteen years ago, to celebrate my mom’s 70th birthday, my immediate and extended family travelled to Haida Gwaii, B.C. for what was truly an adventure for all to remember.

A highlight of this trip was a visit to the exceptional Haida Heritage Centre at Ḵay Llnagaay (meaning “Sea-Lion Town”), which opened in 2008 and was designed after the ancient oceanside Haida village that once stood in its place.

The operation houses several community initiatives, including a carving shed, the Haida Gwaii Museum and programs that support language revitalization.

“We’re now building a community smoke house, a cook pit and traditional fish drying racks, and we plan to open a local market,” says Dana Moraes, executive director of the Gwaalagaa Naay Corporation, which oversees the centre.

“And we’re going to be offering community workshops which will see the transition of knowledge from elders and knowledge keepers to community and youth.”

Moraes says the centre — which is actively looking at alternative energy sources to improve its ecological footprint — is also involved in projects exploring traditional food security, climate change and adaptation.

“Food security and weather are integral to Haida culture,” says Moraes, who recently attended an Indigenous climate resiliency conference hosted by Alderhill (a company that specializes in Indigenous community planning) in conjunction with the B.C. government.

“Indigenous people have been around for tens of thousands of years. We’ve had to adapt to climate. When we greet each other in Haida, we ask ‘How is the weather today?'”

Photo of Mike Willie by Taylor Burk with Sea Wolf Adventures / Port McNeill, B.C.

Sea Wolf Adventures

We first profiled Mike Willie of Sea Wolf Adventures five years ago in a feature Q&A called Travel, truth and beauty.

His company, which is based out of Port McNeill, B.C. on Vancouver Island, invites travellers to join the Kwakwaka’wakw on boat-based journeys throughout the Broughton Archipelago and Great Bear Rainforest “to meet the awe-inspiring animals and incredible humans who call this beautiful territory home.”

From the get-go, Willie’s company — which includes watching wildlife such as whales, grizzlies and sea lions through a cultural lens — has operated with the bigger picture in mind. But mainstream words like “sustainability,” he says, don’t do justice to an Indigenous worldview.

“We are one with the land. Nothing out there is as deeply connected as when we as Indigenous people work the land, protect it and take care of it. We’re not just ‘ecologists’ or ‘conservationists’ or ‘sustainable tourism operators.’ We were born from this land. It’s in our DNA and in our legends,” says Willie.

“Sometimes, it’s hard for others to understand the Indigenous paradigm. There’s a lot of ebb and flow. It’s fluid. You can see it, and you can hear it in our language. When you see our boats on the water, you need to know that we’re different because we are from here.”

Although Sea Wolf Adventures is a business, Willie insists making a buck isn’t the bottom line for him.

“It’s about building capacity and training and providing employment for our community. To see my niece and my nephews working, to see how happy our employees are when they’re out on their ancestral lands and water? That’s medicine for me.”

As for the grizzlies that guests are able to observe and learn about while on tour with Sea Wolf Adventures, Willie sees them “as brothers and sisters, almost like human beings with animal skins. To encounter them is always moving. They’re our ancestors.”

Photo courtesy Knight Inlet Lodge / Knight Inlet, B.C.

Knight Inlet Lodge

Owned by five partner First Nations — the Da’naxda’xw Awaetlala, Mamalilikulla, Tlowitsis, Wei Wai Kum and K’ómoks — Knight Inlet Lodge is an internationally renowned floating wilderness resort located 240 kilometres northwest of Vancouver.

“We were the first grizzly bear viewing lodge in B.C. and we continue to support grizzly research and conservation projects,” says general manager Brian Collen, adding that lodge efforts helped end the grizzly bear trophy hunt in B.C. in 2017.

“We’d been trying to stop the grizzly bear trophy hunt for years. The government listens to economics. We were able to demonstrate that grizzly bear viewing in the province raises 10 times more for government coffers than what the hunt was contributing.”

Given the lodge’s ownership structure, the operation bills itself as offering “the wisdom of thousands of years of Indigenous stewardship,” while providing guests with comfort, fine food, wildlife viewing and spectacular scenery that includes glacier-fed waterfalls and ancient rainforests.

The operation, a short floatplane ride from Campbell River on Vancouver Island, is sheltered in the waters of Knight Inlet, the longest fjord on Canada’s West Coast.

Knight Inlet Lodge is also engaged with Pacific salmon conservation work — including restoration projects to help ensure food security for grizzly bears in the region.

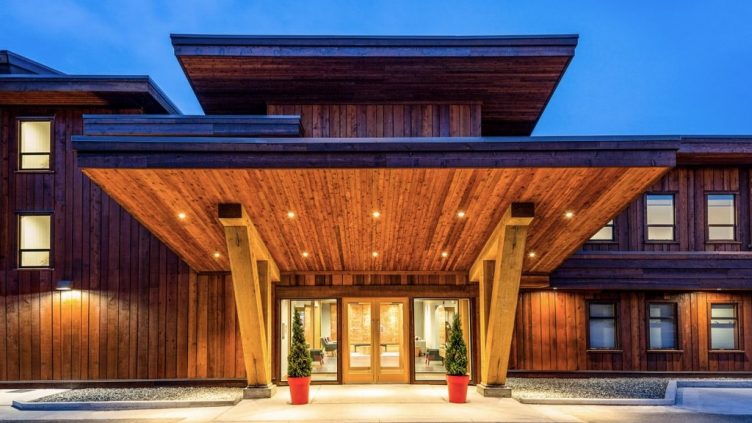

Photo courtesy Kwalilas Hotel / Port Hardy, B.C.

Kwa’lilas Hotel

The Kwa’lilas Hotel in Port Hardy, B.C. is located on the traditional territories of the Kwakiutl people.

The name “Kwa’lilas” — a kwak’wala word used by the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw meaning “place to sleep” — was chosen by local elders in hopes that visitors would find “a peaceful rest” at the hotel after exploring Northern Vancouver Island.

Inspired by a traditional big house design with a smoke hole in the top (traditionally, smoke was a welcoming sign), the property was constructed by the k’awat’si Construction Company — which is under the umbrella of k’awat’si Economic Development LP (KEDC).

“We have our own aqua programs where we farm oysters, scallops and mussels and we source our own wild salmon, which we smoke in our own smoking houses,” says KEDC’s tourism general manager Enrique Toledo of the enterprise, which is home to two restaurants.

A Vancouver Island-based Mayan from Guatemala (where, like Indigenous people in Canada, “we also have a deep connection to nature”), Toledo says the hotel is led by five principles, illustrating a holistic approach to business and community.

“We consider personal development and mastery,” he explains. “We make an effort to understand our history and our community’s vision. We understand that we are intertwined. We work, consistently, to deliver together. And, we work and learn as a team, not in isolation.”

Recently, the Kwa’lilas Hotel was excited to launch a culinary program in the community’s elementary school. “We’re cooking from scratch, breakfast and lunch, for 240 kids daily,” says Toledo.

Photo by Mary Putnam with Big Bar Guest Ranch / Near Williams Lake, B.C.

Big Bar Guest Ranch

Owned by Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation (SXFN), Big Bar Guest Ranch invites you to canoe, ride horses, hike and enjoy cultural experiences on the operation’s picturesque 100-acre property.

The historic ranch is located in a semi-remote area on the Fraser River, approximately 85 kilometres southwest of Williams Lake, B.C. The community that owns it is made up of two distinct bands — Canoe Creek (Stswecem’c) and Dog Creek (Xgat’tem) — that joined together in the late 1800s, while honouring their separate histories.

Today, the ranch operates with the intention of becoming a self-sustaining community that features living Indigenous culture, language and traditions.

Ranch manager Jenna McKague, an enthusiastic spokesperson for the property, says all manner of animal can be found onsite — horses, dogs, cats, chickens, ducks, turkeys, rabbits, pigs and goats.

“We have honey bees, too, to help with the pollination of the plants that we grow in our vegetable garden. We’re doing everything we can to support permaculture on our land,” says McKague, referring to a style of land management that observes systems found in thriving natural environments.

The ranch recently secured funding to help construct a pit house — a log and earth structure built into the ground that reflects traditional Indigenous housing from the region — as an onsite cultural attraction.

“It’s a large project. The funding will help us find an engineer with pit home experience to design a blueprint — as well as find someone in a local First Nation’s community, if not our own, to construct it,” she says. “In time, we’d like to rent it out to guests as accommodation.”

James Cowpar of Haida Style Expeditions / Photo courtesy the Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada

Haida Style Expeditions

It’s impossible not to want to jump on a plane and head to Haida Gwaii after having a phone conversation with James Cowpar of Haida Style Expeditions.

Cowpar’s goal with travellers is to have them visit the remote archipelago as tourists but “walk away as family.” With fishing and cultural tours and by offering authentic Indigenous experiences, he genuinely wants to inspire people and change the world.

“If spending time with Haida Style Expeditions can promote change and teach respect for all living things, which is the Haida way, and dissolve stereotypes around First Nations people, then that’s the most meaningful thing we can do,” says Cowpar.

“This approach will pave the way for my children and future generations. The planet needs to start paying attention to Indigenous ways,” he says.

His company, which he co-owns with his twin brother William, is based on a system of values, with the art of exchange at its core.

“We have built and continue to build our business with the idea of reciprocity. If we’re going to take, we’re also going to give back in a meaningful way.”

Case in point? Cowpar recently joined a marine debris initiative on Haida Gwaii, with the help of 20 local youth.

“We collected close to 40 super sacks, which can weigh up to 400 pounds each. Some people found Yeti brand coolers from a cargo ship spill. I’m still waiting to find mine!”

Photo by Ian Harland with Coastal Rainforest Safaris / Port Hardy, B.C.

Coastal Rainforest Safaris

Coastal Rainforest Safaris is owned by Mike Willie of Sea Wolf Adventures (profiled earlier in this feature) and Andrew Jones of Kingfisher Wilderness Adventures.

“People travel the planet to go on safaris but we have safaris right here in B.C.,” says Jones of the Port Hardy-based operation.

“We like to look at whole ecosystems — so not just orcas, but humpback whales, sea lions and sea otters, and even sea stars and sea urchins. We also take guests to shell middens, which show how people have historically shaped the ecosystem.”

Both Jones and Willie have been recognized as standout operators who offer what Destination Canada (a crown corporation that promotes Canadian tourism) classifies as Canadian Signature Experiences.

Between them, they bring a wealth of experience in customer service, wildlife viewing and cultural interpretation to Coastal Rainforest Safaris.

“Mike and I working together is not a token gesture,” says Jones. “It makes sense from a social responsibility perspective. I hope we see more of us, people working together, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, on northern Vancouver Island.”

Their company’s goal, says Jones, is to get visitors thinking about the greater world as a whole.

“Whether it’s better understanding Indigenous cultures or protecting wildlife. We really want to help grow tourism in a positive way. Tourism out here is about so much more than just seeing charismatic mega fauna like orcas, as amazing as they are.”

Image by Full Moon Photo with Haida House / Haida Gwaii, B.C.

Haida House at Tllaal

Twelve new oceanfront cabins were unveiled this year at Haida House, a lodge based in Haida Gwaii, B.C. and owned by the Haida Enterprise Corporation (HaiCo).

“They’ve each got two rooms and a different forest or ocean view,” says HaiCo marketing and communications manager Shawna McKay. “They’re a higher end, more private option for guests.”

Haida House — a former hunting property located on Graham Island’s dramatic east coast — features 10 rooms accommodating 22 guests, while the lodges’s new cabins, located nearby, can accommodate up to another 48 guests, with up to four people per unit.

Visitors are offered a variety of packages that include from three to seven night stays, with itineraries centred around local food, art, culture and nature.

“Environmental, social and cultural aspects of the business are the big thing with us. We’re designed to reflect Haida cultural values, hire local and strengthen the Haida Gwaii economy, but with sustainability in mind,” says McKay.

“We’re proud to have received a “Gold Level” tourism designation for our efforts to green up Haida House.”

McKay encourages people to take the Haida Gwaii pledge before visiting the remote archipelago, which is often referred to as “Canada’s Galapagos.”

Meanwhile, she says the lodge can’t wait to get back to business as usual. “Given the pandemic, it’s been a long time. There’s a lot of pent-up demand. This is going to be an exciting season.“

Photo by Destination Canada with Klahoose Wilderness Resort

Klahoose Wilderness Resort

An off-the-grid wilderness operation in B.C.’s Desolation Sound, Klahoose Wilderness Resort is owned by the Klahoose First Nation.

“Everything we do is with an Indigenous focus, whether we’re talking about what guides share with you on a boat tour or whether we’re pulling up prawn traps,” says resort tourism manager Chris Tait.

“When you arrive, you’re welcomed with a traditional song. This sets the tone for the entire stay.”

According to Tait, a cultural interpreter remains onsite for the duration of a guest’s visit.

“It’s about giving visitors a connection to an Indigenous person who is local to the area so they can have an honest conversation about just about anything, which is key to what we’re doing,” he explains.

Travellers to the resort can buy packages, depending on their interests, and then arrive either by boat from Lund, B.C. or by sea plane. Experiences available range from helicopter tours to fishing and grizzly viewing.

During their stay, guests can also take self-guided rainforest walks, paddleboard, kayak and partake in cultural experiences that include cedar weaving.

“We are located in what’s called Homfray Channel. The Klahoose name for the channel is ‘Thee chum mi yich,’ which means ‘further back inside,'” says Tait, adding that given the location’s geography, surrounding ocean waters — some of the warmest north of Mexico — are great for swimming.

“As for our operations, we’re constantly evolving,” says Tait of the resort, which is committed to supporting glacier, watershed and ocean health research, as well as a mentorship program for Indigenous youth pursuing careers in tourism.

“This year, we added a new micro hydroelectric project that should eliminate 38 tonnes of carbon emissions.”

Editor’s note: This story is the result of an arm’s-length collaboration between the Indigenous Tourism Association of British Columbia and Toque & Canoe.

Toque & Canoe is an award-winning digital platform featuring stories about travel culture in Canada and beyond.

Feel free to follow us on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook